Project Overview

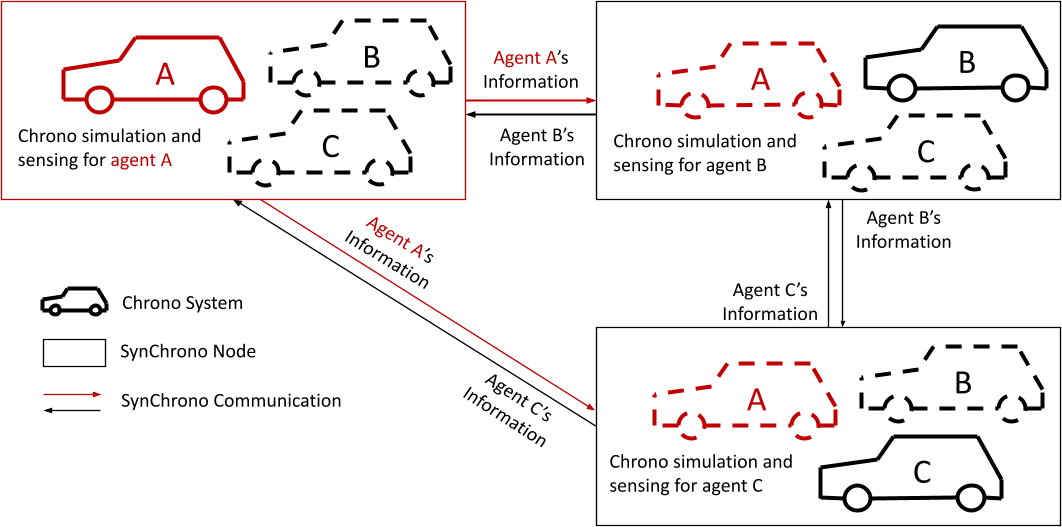

SynChrono is an autonomous vehicle simulation project developed by the Simulation Based Engineering Lab (SBEL) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This simulation framework is based around the ability to simulation one or multiple robots, autonomous vehicles, or other autonomous agents together in a unified framework. Our current motivation comes from autonomous vehicle testing, so many of our demos and examples will draw on autonomous vehicles, but since the simulation is backed by Chrono, we can support any virtual environment.

Our goal is to extend Project Chrono's physics simulation into the multi-agent realm, specifically the multi-agent realm where the dynamics of the agents are not strongly coupled. For a simulation of say two robots underwater, where the currents created by one robot will impact the dynamics of the other robot, you are better off in Chrono, where the robots and the fluid will be contained together in a single Chrono model and where the dynamics will be jointly simulated. SynChrono is suited for scenarios where the dynamics of each agent are important individually, but not in the way that they interact with each other. This is the case for autonomous vehicles where, barring a collision, the dynamics of one vehicle will not impact any other. SynChrono synchronizes the motion of all agents, but allows their dynamics to be distributed across computing nodes rather than including all dynamics in one monolithic simulation.

Images: On the left a convoy of autonomous vehicles navigate obstacles on offroad terrain using a policy developed through machine learning. On the right an autonomous vehicle performs a lane change in a highway setting.

Agent Synchronization

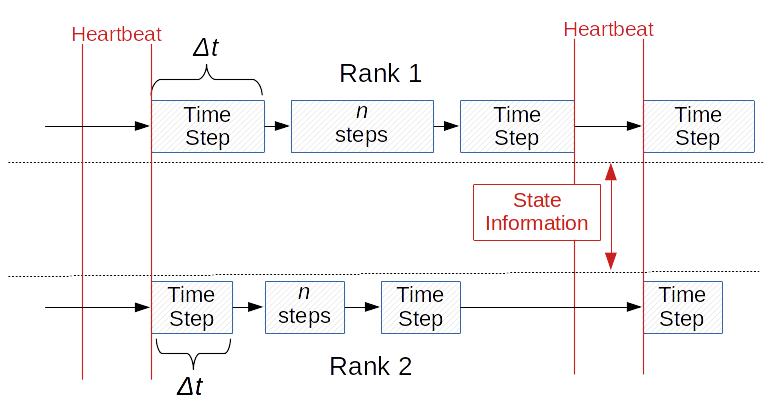

The dynamics of a "typical" Chrono system (for example one using Chrono::Vehicle) are handled by stepping the simulation forward in time by some timestep Δt, where at each timestep, new states are computed for each entity in the ChSystem. This is still the case in SynChrono except that each simulation node handles its own ChSystem, and these separate systems must be periodically synchronized. The situation is illustrated in the figure below:

Each node steps forward in time, at the same constant timestep. Some nodes may move through their timesteps in less real-world time than the others, simply because they have more processing power, a simpler system, or for any other range of reasons. However after a certain number of timesteps have elapsed in simulation, called the heartbeat, all nodes will synchronize their current state. Between heartbeats, the zombie agents in a node's ChSystem are not updated, and will remain static until a heartbeat is reached and updated state information for them is applied to the ChSystem.

Next we explain what exactly is communicated at each heartbeat (State Information), how this data is formatted (FlatBuffers) and how the data is communicated between nodes (Communication Types).

State Information

The state information that is communicated at each heartbeat is specific to each type of agent, it should be the minimum required to construct a zombie agent in the world of another node. For vehicle agents we need to know two things:

- What the zombie should look like

- Where the zombie should be placed

What the zombie looks like is handled through specification of the number of wheels and of mesh files to be used for the chassis and wheels, this happens just once at the beginning of the simulation. Where the zombie is placed gets communicated at every heartbeat, and consists of the position and orientation (pose) of the vehicle's center of mass along with a pose for each of its wheels.

FlatBuffers

To communicate state information between nodes, we need to move data about each agent from C++ objects, to a series of bytes that travel over the wire between nodes. FlatBuffers is a library that handles exactly this serialization and deserialization of data.

Any agent that will be synchronized must have a flatbuffers schema (see example below) that defines how their state data is formatted, and a corresponding class that uses this schema to pack and unpack data into a C++ class.

Communication Types

After the nodes reach a heartbeat and use FlatBuffers to pack their data, a SynCommunicator takes charge of sending this binary data to all other nodes in the simulation for consumption. Currently there are two types of communicator, one based on the Message Passing Interface (MPI) and the other based on the Data Distribution Service (DDS), but others can be defined so long as they handle the task of interchanging data between all nodes in the simulation.

Message Passing Interface (MPI)

Synchronization with MPI is accomplished using two MPI calls. While many types of agents will send messages of a fixed size (vehicles, for example), others (Deformable terrain) will not. For this reason, nodes don't immediately know how much space they'll need for incoming state data. MPI synchronization uses a first call to determine how much space each node will need for their state data, and a second call to collect that data after the nodes have allocated space to receive it. More details are in the MPI synchronization section of the manual.

Data Distribution Service (DDS)

Synchronization can also be accomplished using DDS. Rather than the collective communication of MPI, DDS communication is point-to-point via a collection of "topics", one for each node's state data. To synchronize state, each node subscribes to topics for all other nodes. DDS takes advantage of multi-threading to handle sending and receiving from multiple nodes at once. DDS is usually preferred over MPI outside of cluster situations, where MPI is less available and more communication flexibility is required as DDS can communicate using UDP. More details are in the DDS synchronization section of the manual.

Support for Other Chrono Modules

The focus during SynChrono's development has been on autonomous vehicle simulation, so SynChrono currently depends on Chrono::Vehicle for proper operation. While this is not a fundamental limitation, there are also no additional dependencies required to build Chrono::Vehicle so this dependency should not be a burden.

SynChrono supports visualization through both the Chrono::Irrlicht and Chrono::Sensor modules.